Impact of the Built Environment

The built environment can increase inclusion or promote exclusion. Would Paris or New York be as appealing to stroll around without their well-kept streets, public transportation systems, and benches?

Large-scale infrastructure in cities such as roads, bridges, and tunnels have an obvious and immediate impact on how residents move around the urban landscape.

On a smaller scale, the built environment on the street level has an even greater impact. Think about how you interact with some of the great cities in the world. Would Paris or New York be as appealing to stroll around without their well-kept streets, public transportation systems, and benches?

The built environment can increase inclusion or promote exclusion. Park benches, bike racks, and rubbish bins are critical tools in the human-centric urbanist’s arsenal. As Oslo, for example, tries to make its city centre car free, the need for street furniture has exploded.[1]By getting people out on the streets and in green places, Oslo is embracing a core tenet of the human-centric push in urbanism.[2]Access to green and open space transforms the emotional and social lives of residents. It further reduces stress and leaves residents happier, more productive, and satisfied.

Inversely, some cities are using street furniture and other elements of the built environment to exert greater control over the movement of people in the city.[3]As the homeless populations in major cities

have exploded, some municipalities have taken extreme steps to design hostile urban landscapes. Park benches with dividers to prevent someone from lying down, or the use of gates and barriers to restrict access to building entrances, are two such examples of hostile architecture, an increasingly popular instrument against homelessness.[4]

The built environment deeply influences resident’s lifestyle, habits, and even health. For a large portion of the 20th century, urban growth and development focused on low-density, car-dependent residential communities. The resultant urban sprawl had a clear impact on the health and happiness of urban communities, as researched by Howard Frumkin in his ground-breaking work Urban Sprawl and Public Health.[5]Through a detailed analysis of the adverse effect of low-density sprawl on the health of residents in major American cities, Frumkin emerged as one of the leading advocates for the consideration of individual health in urban planning decisions.

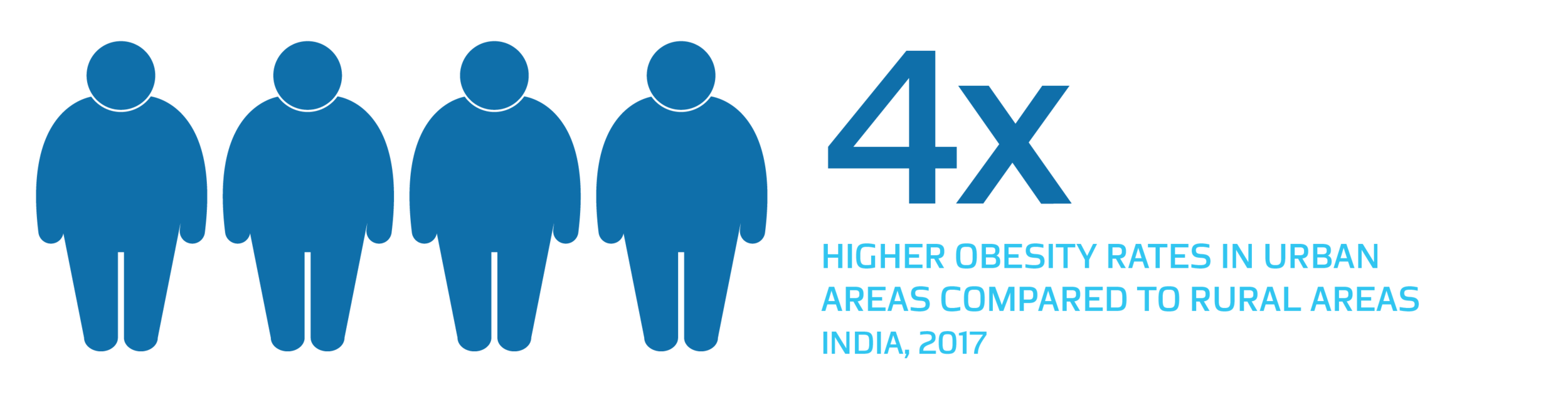

The fast-growing cities of the Arabian Gulf are perfect laboratories to ascertain whether cities can combat lifestyle diseases. Diabetes and other ailments related to obesity are on the rise in the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. As both of these countries invest in infrastructure projects to put their cities on the cutting edge of global developments, they are confronted with significant challenges in combating these diseases. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, and the UAE have some of the world’s highest levels of obesity among adults-, where between 27% and 40% of the population is being affected.[6]In the UAE, one in three children are either obese or overweight. This is particularly concerning as childhood obesity can lead to health concerns later in life.

Given the scale of the problem, urbanists are considering steps to use the city to fight obesity. The urban landscape affects health in myriad ways including the nature of housing and transportation options, planning and zoning provisions, and the number of parks and amount of open space. Interaction with the natural environment in terms of the quality of air and water also bears heavily on our overall health. The World Health Organization also notes that social capital, wealth, and the availability of health services are major factors in the connection between urbanism and happiness.[7]

Lack of physical exercise is one of the primary reasons obesity and other lifestyle diseases are on the rise. The urbanist challenge in this regard is straightforward: get people moving. City designs that encourage walking between shops, schools, and parks through well-maintained sidewalks and bike lanes are a proven method. In the UAE, where the harsh summer climate discourages walking outside, initiatives to get people moving indoors have proven successful. From the construction of state-of-the-art indoor sporting facilities to 5-km runs inside shopping malls, creative initiatives are helping to get people moving.

However, efforts to leverage the built environment to combat obesity are often stymied by the omnipresence of technology. Technology is pervasive in society, for better or worse. Internet penetration in the GCC is among the highest in the world. Speaking with The National newspaper, Alaa Takidin, a clinical nutritionist, said that “even though parents are striving to find a healthy balance between technology, food intake, and overall lifestyle of their children, we still come across a lot of child obesity cases. This is mostly related to overuse of gadgets, lack of physical activity and unhealthy eating patterns. Technology is one of the main culprits behind the lack of physical activity, as kids find it more interesting to play games on smartphones rather than engage in outdoor activities.”[8]

While we might not think of the internet as part of the built environment, access to the web is a critical infrastructure of the modern city. Therefore, we can think about the use of technology in a similar way that we consider the built environment. The more we are consumed by looking at our screens, the harder it is to get outside or get moving towards a healthy lifestyle.[9]

The next question becomes, how to balance built infrastructure with the virtual infrastructure of the ascendant smart city? Are we at risk of losing our humanity in cities with the rise of machine

technology designed to make our lives easier?

[1] Alagiah, Matt. “Space Race” Monocle, July 2018, https://monocle.com/magazine/issues/115/space-race/

[2] Carsten Jahn Hansen. The New DNS of Danish Spatial Planning Culture. London: Nordic Experiences of Sustainable Planning, 2018

[3] “Hostile Architecture: an uncomfortable urban art” The Guardian, 21/08/2018, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2018/aug/21/hostile-architecture-an-uncomfortable-urban-art-in-pictures

[4] Ibid

[5] Howard Frumkin, Lawrence Frank and Richard Jackson. Urban Sprawl and Public Health: Designing, Planning, and Building for Healthy Communities. New York: Island Press, 2013

[6] Gillet, Katy. “Saudi Arabia Brings in Mandatory Calorie Labels on Menus” The National, 2/1/2019,

https://www.thenational.ae/uae/health/saudi-arabia-brings-in-mandatory-calorie-labels-on-menus-1.808556

[7] Webster, Nick. “UAE’s High Child Obesity Rates Blamed on Technology” The National, 23/7/2018,

https://www.thenational.ae/uae/uae-s-high-child-obesity-rates-blamed-on-technology-1.753203

[8] Ibid

[9] Rainwater, Brooks. “Rethinking Our Cities to Fight Obesity” Fast Company, 30/1/2014,

https://www.fastcompany.com/3022922/rethinking-our-cities-to-fight-obesity