Evolution of Human-Centric Urbanism

While the happiness of residents wasn’t the driving motivation of urban planning in the past, the rise of connected urbanism placed new emphasis on people, their health, and how urbanism can improve lives.

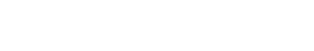

Before the Industrial Revolution, cities were hives of commerce organized to protect the economy. As people poured into urban areas from the countryside in the 19th century, disease and the health of residents became a grave concern for municipal authorities trying to keep the economy growing at full speed.[1]

While there was a much greater focus placed on defence in pre-modern cities, with commerce taking second place in the minds of urban planners, the Industrial Revolution was a watershed moment in the history of urbanism.[2]

As cities entered the age of modern capitalism, tension arose that pit urban sustainability against economic boom and bust cycles. In this context, sustainability has meant a host of measures related to the long-term health of cities being taken, including the protection of the natural environment, sufficient sewage systems equipped to handle large numbers of residents, lack of congestion, and ample infrastructure. But only recently has the notion of happiness for city dwellers emerged as a sustainable concern for city authorities.

Urban sustainability is expensive considering the nature of economic cycles and their periods of excess and poverty. Communist models, it should be noted, were less subservient to the boom and bust of capitalist societies, and placed much greater emphasis on utilitarian planning designed to maximize efficiency and uniformity for the working class. However, this style produced brutalist architecture and sterile urban landscapes that engender isolation rather than cure it.[3]

During boom cycles in capitalist frameworks, there are more resources are allocated to focus on sustainability, including planning for the happiness of individuals. However, during periods of contraction, economic growth takes precedence across society, including in urbanism. Given the relatively long period of economic growth over the last two decades (with full recognition of the 2008-09 economic downturn), urbanism as a field and discipline has found resources to focus on sustainability and human-centric design in wealthier countries. This is one reason why urbanism has become an intense topic of interest, even for non-professionals.[4]

Yet, planners have struggled to maximize the efficiency of the urban environment within these parameters. While the happiness of residents wasn’t the driving motivation of urban planning in the past, the rise of connected urbanism placed new emphasis on people, their health, and how urbanism can improve lives. With the technological innovations of the late 20th century in Western cities, these concerns have slowly but surely shifted the focus of urbanists around the world.

The popularity of private automobiles and America’s incredible post-World War II wealth led to another seismic change in how urbanists understood the cities of the 1950s. Infrastructure developments including freeways, strip malls, and housing projects (not to mention newly created suburbs) hollowed out many of America’s cities.[5]Wealthier life was moved outside of the urban environment, which in turn was left to decay from lack of resources. The automobile meant that cities needed large road systems and parking lots that could service this new form of transportation. Collective city life, whether in the form of public transportation or city parks, suffered greatly during this period. While this transformation was uniquely American, it made waves throughout the world as other cities attempted to reconstruct themselves to make the use of cars more efficient.

These transformations were also met with some resistance. Jane Jacobs, the journalist and grassroots organizer in New York City, famously critiqued Robert Moses’ top-down and car-oriented approach to urban planning with a call for greater focus on communities and pedestrians. Jacobs wanted cities to remain diverse and committed to the principle of community.[6]Destroying neighbourhoods to make way for highways served few needs, she vociferously argued. Their famous debate gave birth, in a small but significant manner, to the human-centric developments we see unfolding in urbanism today. Jacobs motivated the pioneering work of urbanists and architects such as William Whyte, Lewis Mumford, and Kevin Lynch.

It might seem simple to focus so intently on the automobile when discussing human-centric urbanism, but the role of the car continues to have an outsized impact on how cities are constructed. As urbanists turn their sights on human-centric plans, breaking down the automobile’s dominance in the urban environment has been a central focus. Take Barcelona’s super blocks as one of many examples of this principle in action. To cut down pollution, Barcelona has embarked on an ambitious plan to reduce the number of cars in the city while simultaneously using reclaimed streets for pedestrian walkways and markets.[7]The result is more economic activity, more people walking, and happier residents. As Lewis Mumford wrote in The Highway and The City, “the right to have access to every building in the city by private motorcar in an age when everyone possesses such a vehicle is actually the right to destroy the city”.

Put in another way, the car is disruptive technology from a different time that we are still trying to tame. Today, there are a host of other technological innovations that will have similarly profound effects on urbanism. As cities exploded in population over the last decade and the internet’s promise to streamline human life by offering bespoke services on demand has positioned it at the centre of human existence, human-centric urbanism has adopted a new immediacy. The city will define the next chapter of human civilization, just as it has in the past.

In the last decade, human-centric urbanism has undergone a significant transformation, advanced by the rise of internet connectivity, artificial intelligence, and other technological innovations that have given planners the tools to create a city that encourages social growth and facilitates well-being.

[1] Buehler, Michael. “The Fourth Industrial Revolution is about to hit the construction industry. Here’s how it can thrive” World Economic Forum, https://europeansting.com/2018/06/14/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-is-about-to-hit-the-construction-industry-heres-how-it-can-thrive/

[2] Dennis, Richard. “Urban modernity, networks, and places.” History in Focus. February 2018 https://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/City/articles/dennis.html

[3] Beyond Brutalism: Creative Modernist Concrete Architecture”WebUrbanist, 04/01/2009

https://weburbanist.com/2009/04/01/brutalism-postmodernism-concrete-architecture/

[4] Dennis, Richard. “Urban modernity, networks, and places.” History in Focus. https://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/City/articles/dennis.html

[5] Foth, Marcus. “Connected urbanism and cohabitation in the smart city” in Hollo, Tim (Ed.) Proceedings of the Green Institute Conference 2017: Everything is Connected, The Green Institute, Canberra, A.C.T. (In Press)

[6] Burkeman, Oliver. “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro review– a landmark study” The Guardian, 23/10/2015 https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/23/the-power-broker-robert-moses-and-the-fall-of-new-york-robert-caro-review

[7] Foth, Marcus. “Connected urbanism and cohabitation in the smart city” in Hollo, Tim (Ed.) Proceedings of the Green Institute Conference 2017: Everything is Connected, The Green Institute, Canberra, A.C.T. (In Press)